Day One: OPENING Loudly

Type has a voice, and Hank Ricardson’s students learn that by standing on table and yelling at the top of their lungs.

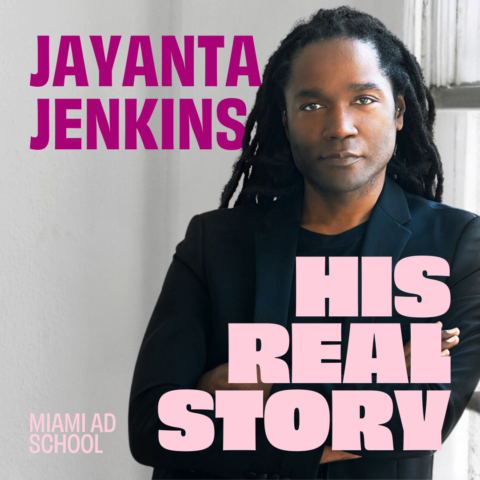

L to R: Art Direction student Gina Cassaro and Graphic Design students Sarah Asip, Carter Tindall and Cydney Schwartz.

It’s a competition. Students attempt to one-up each other, their voices resonating and, as a result of this infectious interaction, students remember what they learn. At the same time, they gain invaluable presentation skills and their confidence soars.

On the first day of the quarter, it was my duty to fill-in for a teacher—an associate creative director—who had a client meeting to attend. When I teach beginning typography, I have an exercise the I dreamed up to communicate the impact of the many choices you can make in type design.

I use the text of an old annual report as a script. If you’re going to be an actor, you’ve got to have a script, after all. The report was designed by Dana Arnett of VSA Partners for the Chicago Board of Trade. In its time, the annual was considered revolutionary for its dynamics of color, impacting scale and its ability to use typography to tell a story. I’ve had many students participate in this exercise over the years, and each time it is an awakening to the excitement of what typography can be.

As I walked in the classroom I declared, “Let’s learn something about typography!”

I asked an upper-quarter student, Emily Kemp, to help me. I looked pointedly across the table to four students—Gina, Sarah, Carter, and Cydney.

“You, you, you and you—up on the table!” I barked, and handed them the annual report as they climbed up.

“Now Gina, read the cover,” I said.

“Open,” said Gina.

“Is that really how it looks and sounds?” I asked.

“Open,” said the student, a little louder.

“LOUDER,” I exclaimed.

“Open!”

“LOUDER! LOUDER!”

“OPEN!”

“Good,” I said, as I grabbed the annual report and passed it to Cydney.

This went on for a dozen spreads as each student read the text as they would if auditioning for a play, with me urging them on as the demanding director.

None of these newbie designers will ever forget that typography has a “physical” voice, not just a position on a page. Typography is like frozen music—it has volume and pacing, rhythm and cadence—depending on how it is set and composed by the designer.

Heavy.

Little.

Thin.

Big.

Small.

Caps.

Red.

Lowercase.

Serif.

Sans-serif.

Black.

Colored.

Reversed.

Letter-spaced.

Leaded.

Contrast.

White space.

Hierarchy.

Pushed to the top of the page or perfectly centered.

Each aspect, each detail, each small decision plays a role.

It was quite a dramatic typography lesson.

The teacher I was substituting for—Jack Whitman, a graduate—once acted in this “Theater of Typography.” I bet he still remembers. Jack’s an amazing designer (and also an amazing type designer). He now works here in Atlanta at Son & Sons.

The great thing about this exercise—no one ever forgets. It’s one of those events that carry more meaning than what meets the eye and the ear. No matter if the student turns to the quietest page or the largest and noisiest one, the voice of the page is given life.

A thorough grasp of typography is one of the most crucial skills a designer might acquire. It’s the primary tool for communicating a message. As educators and professional designers, I believe it’s our duty to get this idea across in a way that is meaningful, memorable and moving. After all, imagination comes from things that move us.